Bridges are classic examples of engineered structures—so much so that countless computer games and in-class activities for K-12 students consider what kinds of supports and shapes provide the greatest strength.

That said, bridges are much more than spans of wood, stone, iron, or steel that allow people and vehicles to cross from one point to another. When considered carefully, each bridge reveals much about its own construction and what its designers, builders, and users valued.

Next week, we will learn more about how to “read” (analyze and interpret) engineered artifacts such as bridges. For now, however, I’m going to tell you a little bit about bridges—two of them in particular—and ask you to share your own thoughts about them in a blog post.

Crossing waterways before bridges

Today we take bridges for granted. While the Golden Gate Bridge has come to be the primary symbol of San Francisco, and the Brooklyn Bridge appears in much iconography of New York City, the bridges are, historically speaking, relatively recent additions to these cities. The Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883, during my great-grandparents’ lifetimes. There are still people living who remember the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge. My own grandmother, for example, walked across the Golden Gate Bridge on its opening day in 1937.

Before bridges, U.S. Americans often took ferries across rivers that were too deep, wide, or fast to be forded on foot, horseback, or wagon. There used to be a ferry, for example, where the Capitol Boulevard Bridge stands now in Boise; you learn more about it from this copy of a sign that until recently was posted on the Boise Greenbelt.

Perhaps the most famous depiction of a ferry in American history comes from Walt Whitman’s poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” which describes the experience of crossing the East River between Brooklyn and Manhattan before the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Chances are, since few of you in the class are majoring in the arts or humanities, you’re not huge fans of poetry. That’s OK. However, I want you to read Whitman’s poem, and I want you to read it carefully.

Here’s a recording of me reading the poem that you can listen to while you read it, if you think audio will help you better understand it:

Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

Walt Whitman

Considering Whitman’s poem as an historian would

Because “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” is a work of a poet’s imagination, historians are likely to consider it a reliable account of a ferry crossing when its details can be corroborated by other sources. That said, the narrator (the speaking “I”) of Whitman’s poems is often either Whitman himself or someone very much like him, so it’s very likely “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” is a description of Whitman’s experience, or an amalgamation of experiences, crossing between Brooklyn and Manhattan.

For the moment, let’s set aside the question of whether other sources corroborate the details of Whitman’s poem. Instead, let’s use the poem to notice the kinds of things Whitman does:

- What’s in the sky above him (e.g., seagulls, clouds, the sun)

- What he sees around him (e.g., crowds of hundreds of men and women “attired in the usual costumes”)

- What he sees in the river (e.g., the current, crests of waves, river islands, his own reflection surrounded by “fine centrifugal spokes of light”)

- What he sees ahead of and behind the ferry (e.g., ships, sailors, buildings, foundry chimneys, flags being taken down for the day)

Whitman first published “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” in 1856, under the title “Sun Down Poem,” in the first edition of his masterwork, Leaves of Grass. He would revise (and retitle) it, along with several other poems, in subsequent editions of the collection.

Here’s where the historian begins to ask questions: A first one might be “What did ferries look like?”

We don’t have a photo of an 1856 ferry, but here’s what an East River ferry—this one is the Fulton—looked like in 1890:

The ferry Fulton, circa 1890. Source: Library of Congress.

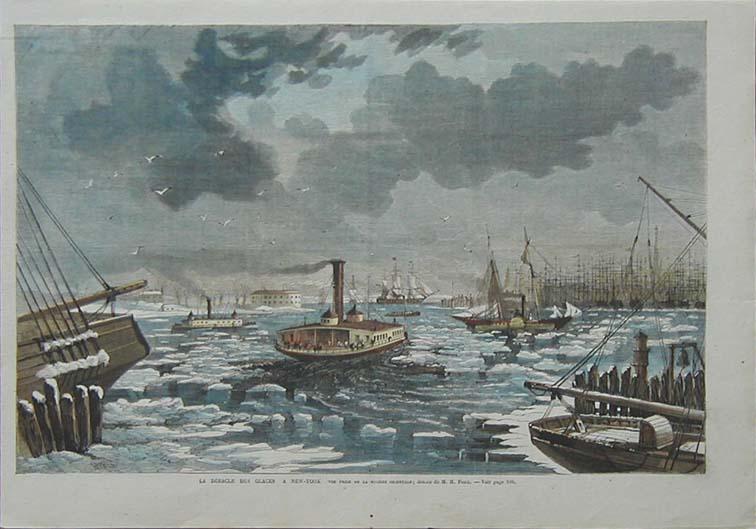

Still, that’s 35 years after Whitman wrote his poem, and we know from our own experiences that technology can change rapidly. Let’s keep searching, then. While we won’t likely turn up any photos, we can find illustrations. A simple image search of the Web, for example, turned up this print of ferries and ships navigating a treacherous, ice-filled East River:

“The Debacle of Ice in New York.” Hand-colored engraving, ca. 1850. Source: Prints Old & Rare.

Whitman’s poem takes place in a less icy river, but the print suggests a bustling waterway like the one illustrated in the poem.

Whitman’s poem is at once about connection—about the movement of bodies, the movement of his body in relation to other bodies—and suspension. Even in his most reflective, introspective moments, the poem’s narrator connects his experience to a common one, writing of literal and figurative shadows, “It is not upon you alone the dark patches fall, / The dark threw its patches down upon me also.” At the same time, he is suspended at a point mid-river, neither in Brooklyn nor Manhattan, neither fully in the present nor yet in the future, where he imagines future residents of New York having the same experiences he has had.

Enter the Brooklyn Bridge

Here Whitman’s poem provides us a lens through which to consider other ways of crossing a river. How better to describe a bridge than as both connecting and suspended, as something that joins and yet remains very much its own thing? In fact, in his essay “Industry, Nature, and Identity in an Iron Footbridge” in the book American Artifacts, Carlos Rotella writes of “bridge epiphanies,” moments of reflective discovery that can happen on bridges. I can think of no better word than “epiphany” to describe Whitman’s narrator’s reflection that we are all part of the same eternal soul.

There are hundreds of ways to tell the story of the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. (An excellent book about the bridge is Alan Trachtenberg’s Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol, which I almost assigned for this course.) For the sake of brevity and ease of reading, I’m going to borrow from Wikipedia’s description and history of the bridge and, against good historical practice, remove citations and link; if you’re interested in the minutiae of the bridge’s construction and maintenance, you can read the fully-cited entry at Wikipedia.*

The Brooklyn Bridge is a hybrid cable-stayed/suspension bridge in New York City and is one of the oldest bridges of either type in the United States. Completed in 1883, it connects the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn by spanning the East River. It has a main span of 1,595.5 feet (486.3 m) and was the first steel-wire suspension bridge constructed. Since its opening, it has become an icon of New York City, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1972.

– Construction of Brooklyn Bridge, ca. 1872-1887. George Bradford Brainerd (American, 1845-1887). Construction of Brooklyn Bridge, ca. 1872-1887. Glass plate negative, 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 in. (8.3 x 10.8 cm). Prints, Drawings and Photographs. Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection, 1996.164.2-1614. (1996.164.2-1614_glass_bw_SL1.jpg)

Construction of the bridge began in 1869 and soon took its toll on its designers and builders.

The bridge was initially designed by German immigrant John Augustus Roebling, who had previously designed and constructed shorter suspension bridges, including some in Pennsylvania and Kentucky. While conducting surveys for the bridge project, Roebling’s foot was crushed when a ferry pinned it against a piling. After amputation of his crushed toes, he developed a tetanus infection that left him incapacitated and soon resulted in his death, not long after he had placed his 32-year-old son, Washington Roebling, in charge of the project.

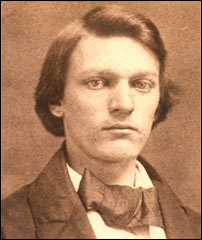

Washington Roebling

Washington Roebling also suffered a paralyzing injury as a result of decompression sickness shortly after the beginning of construction on January 3, 1870. This condition, first called “caisson disease” by the project physician Andrew Smith, afflicted many of the workers working within the caissons. Roebling’s debilitating condition left him unable to physically supervise the construction firsthand.

Roebling conducted the entire construction from an apartment from which he could view the construction, designing and redesigning caissons and other equipment. He was aided by his wife Emily Warren Roebling, who provided the critical written link between her husband and the engineers on site. Under her husband’s guidance, Emily studied higher mathematics, the calculations of catenary curves, the strengths of materials, bridge specifications, and the intricacies of cable construction. She spent the next 11 years assisting Washington Roebling, helping to supervise the bridge’s construction. When iron probes underneath the caisson for the Manhattan tower found the bedrock to be even deeper than expected, Roebling halted construction due to the increased risk of decompression sickness. He later deemed the aggregate overlying the bedrock 30 feet (9 m) below it to be firm enough to support the tower base, and construction continued.

Emily Warren Roebling, manager of Brooklyn Bridge construction and the first person to cross the bridge on its opening day

At the time it opened, and for several years, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world—50% longer than any previously built—and it has become a treasured landmark. Since the 1980s, it has been floodlit at night to highlight its architectural features. The architectural style is neo-Gothic, with characteristic pointed arches above the passageways through the stone towers. The paint scheme of the bridge is “Brooklyn Bridge Tan” and “Silver”, although it has been argued that the original paint was “Rawlins Red”.

At the time the bridge was built, the aerodynamics of bridge building had not been worked out. It is therefore fortunate that Roebling designed a bridge and truss system that was six times as strong as he thought it needed to be. Because of this, the Brooklyn Bridge is still standing when many of the bridges built around the same time have vanished into history.

The Golden Gate Bridge

(Again, much of this section comes from the Wikipedia article on the Golden Gate Bridge. For ease of reading this early in the course, but contrary to good historical practice, I have removed the citations and links. You can find citations on the encyclopedia entry.)

As with the East River, prior to the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, the primary way to cross the Golden Gate—the entrance to the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific—was via ferry. In fact, by the late 1920s, the ferry service across the Golden Gate was the largest in the world. Many wanted to build a bridge to connect San Francisco to Marin County. San Francisco was the largest American city still served primarily by ferry boats. Because it did not have a permanent link with communities around the bay, the city’s growth rate was below the national average. Many experts said that a bridge could not be built across the 6,700 ft (2,042 m) strait, which had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 372 ft (113 m) deep at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.

The design and construction of the Golden Gate Bridge was an interdisciplinary endeavor. Poet and engineer Joseph Strauss took on the role of chief engineer in charge of overall design and construction of the bridge project. However, because he had little understanding or experience with cable-suspension designs, responsibility for much of the engineering and architecture fell on other experts. Strauss’ initial design proposal (two double cantilever spans linked by a central suspension segment) was unacceptable from a visual standpoint. The final graceful suspension design was conceived and championed by New York’s Manhattan Bridge designer Leon Moisseiff.

Irving Morrow, a relatively unknown residential architect, designed the overall shape of the bridge towers, the lighting scheme, and Art Deco elements, such as the tower decorations, streetlights, railing, and walkways. The famous International Orange color was originally used as a sealant for the bridge. (The US Navy had wanted it to be painted with black and yellow stripes to ensure visibility by passing ships!)

Senior engineer Charles Alton Ellis, collaborating remotely with Moisseiff, was the principal engineer of the project. Moisseiff produced the basic structural design, introducing his “deflection theory” by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers. Although the Golden Gate Bridge design has proved sound, a later Moisseiff design, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, collapsed in a strong windstorm soon after it was completed, because of an unexpected aeroelastic flutter. Ellis was also tasked with designing a “bridge within a bridge” in the southern abutment, to avoid the need to demolish Fort Point, a pre-Civil War masonry fortification viewed, even then, as worthy of historic preservation. He penned a graceful steel arch spanning the fort and carrying the roadway to the bridge’s southern anchorage.

Ellis was a Greek scholar and mathematician who at one time was a University of Illinois professor of engineering despite having no engineering degree. He eventually earned a degree in civil engineering from the University of Illinois prior to designing the Golden Gate Bridge and spent the last twelve years of his career as a professor at Purdue University. He became an expert in structural design, writing the standard textbook of the time. Ellis did much of the technical and theoretical work that built the bridge, but he received none of the credit in his lifetime. In November 1931, Strauss fired Ellis and replaced him with a former subordinate, Clifford Paine, ostensibly for wasting too much money sending telegrams back and forth to Moisseiff.Ellis, obsessed with the project and unable to find work elsewhere during the Depression, continued working 70 hours per week on an unpaid basis, eventually turning in ten volumes of hand calculations.

Construction began on January 5, 1933. The project cost more than $35 million, and it was completed ahead of schedule and $1.3 million under budget.

The bridge-opening celebration began on May 27, 1937 and lasted a week. The day before vehicle traffic was allowed, 200,000 people crossed either on foot or on roller skates. On opening day, Mayor Angelo Rossi and other officials rode the ferry to Marin, then crossed the bridge in a motorcade past three ceremonial “barriers”, the last a blockade of beauty queens who required Joseph Strauss to present the bridge to the Highway District before allowing him to pass. An official song, “There’s a Silver Moon on the Golden Gate”, was chosen to commemorate the event. Strauss wrote a poem that is now on the Golden Gate Bridge entitled “The Mighty Task is Done.”

Teenaged sisters Estelle and Dorothy Dannheim dressed up to cross the Golden Gate Bridge on its opening day.

My grandmother, at right in this photo, had borrowed the boots to complete her cowgirl outfit, and for the rest of her long life she would remember how they were a bit too small and caused her a good deal of pain. I often contemplate what it must have been like to walk across that windy bridge; did the crowds jostle her, how did she keep her hat on, and during her long walk across the bridge, did she ever remove those painful boots? As a nearly 15-year-old girl in a progressive coastal city—she was in at least the third generation of her family to live in San Francisco—not long after women earned the right to vote, what would have been her bridge epiphany?

Fifty years later, on its anniversary, the bridge was once again closed to automobile traffic. The commemoration proved almost too popular; so many pedestrians crossed the bridge at one time that the bridge’s center span flattened under their weight.

The Golden Gate Bridge today. Source: Wikipedia.

Your assignment

- Explore historical and present-day photos of these two bridges at Flickr (Brooklyn Bridge and Golden Gate Bridge) and Wikipedia (Brooklyn Bridge and Golden Gate Bridge).

- Write a 300- to 600-word blog post that:

- briefly compares and contrasts the two bridges’ designs, environs, and how people choose to frame and depict the bridges in their photos;

- hypothesizes what the differences in the bridges reveal about the times in which they were built;

- hypothesizes what the persistence of these bridges (each has been renovated and reinforced, but not redesigned or replaced) suggests about the beliefs and/or values of New York City and San Francisco.

If this assignment seems a bit overwhelming, take a deep breath and try to relax. I’m not expecting you to turn in an exceptional analysis of the bridges at this point. Rather, I’ll be using this post to see where your skills in visual interpretation are at the beginning of the course. (This kind of exercise is called a formative evaluation, and I’ll be using it in part to measure your growth in historical interpretation over the semester. You will not receive an individual grade on this blog post.)

Publish your post on the course site no later than Sunday, January 17 at 11 p.m.

Very important: Remember to check the appropriate category boxes under “Groups” and “Student Contributions” in the right-hand column when you’re writing your post. In this case, that would be your group number and the category “01.2 Your Lens.”

Once you have published your post, please comment on your group members’ posts. Assuming your group members have categorized their posts correctly, you can find your group members’ posts by selecting the drop-down menu under “Groups” in the right-hand column.

*For the purposes of your writing in this course, Wikipedia is a fine place to start one’s research, as long as one looks to its footnoted sources rather than citing the encyclopedia entry itself. Here, however, I’m remixing parts of the text, which is licensed under Creative Commons, into an open educational resource that can be used by anyone.

License: Much of the content on this page, with the exception of the photos of the Dannheim family, is either in the public domain or Creative Commons licensed CC-BY-SA. Much of the CC-licensed material is remixed from Wikipedia.