Well, it’s our last week of HIST 100, so I wanted to take a moment to reflect on the course as well as wrap up our study of The Devil in the White City.

A review of where we’ve been

As all Disciplinary Lens courses are supposed to do, we began the course with an exploration of what historians do—the various methods they use to make sense of the past and what they hope to achieve through the use of these methods. While most historians spend a good deal of their time reading, analyzing, and interpreting texts, we focused instead on what we can learn by studying other fragments of the past: artifacts, images, structures, and all kinds of material culture, including the mass-produced, everyday items we find in our own bathrooms.

We then delved into feats of engineering, largely from a much earlier time than ours, examining huge sacred structures like the Hagia Sophia and the Taj Mahal and Incan and Aztec temples, as well as more modest yet still impressive and well-crafted structures like Japanese temples and Quaker meetinghouses. Many of you, when you signed up for this course, might have imagined we’d be looking at the physical/civil engineering of these structures—at how they were built, by whom, and when. And while we have considered such facts, we focused instead on why and what the structures meant at the time of their building and what they continue to mean to their users and visitors in the present day. In short, we began to explore what we could learn about cultures by looking at the things those cultures built.

We veered next into a study of water systems, looking at different systems developed across time and around the world: Spain, the Middle East, and the American West. We began to realize these systems not only represented sometimes monumental feats of engineering, but also political and cultural engineering. Who had the means to engineer these often massive systems? Who took water from whom? Who received the most water, and why? And how did all of these practices and inequities reveal the habits, beliefs, and values of each culture?

The 1893 World’s Fair

Finally, in what might seem at first like a bizarre leap, we went from exploring practices that have been at the core of human life for millennia—sacred spaces and access to water—and “visited” the World’s Fair of 1893, the Columbian Exposition. The Fair exhibited cultures and cultural artifacts from around the world, but it was designed to tell a story about the United States’s cultural and especially technological supremacy. Much of the Fair itself represented the pinnacle of American ingenuity—the massive dynamo engines powering the Fair and the Ferris Wheel come immediately to mind—but the Fair also engineered a literal façade of architectural supremacy in The White City, many of whose buildings’ exteriors were not much more than papier mâché and which, as we learned, were quite flammable.

These constructions all represented, in various ways, beliefs and values many Americans shared or wanted to share. The Fair was an engineered cultural experience meant to educate and entertain, but also indoctrinate visitors with ideas about white Americans’ locations in a global hierarchy of cultural achievement and worth.

Through The Devil in the White City, we also learned of the construction of an edifice representing one man’s twisted values: Holmes’s “murder castle,” the World’s Fair Hotel. However—and you may have seen this query coming—we also need to ask ourselves larger, cultural questions about Holmes’s hotel, primarily what cultural forces allowed this grisly scenario to occur?

To answer that question, we need to ask several others: Over the previous decades, what aspects of U.S. culture developed that allowed Holmes to have the resources and knowledge to build such a structure? How did U.S. culture and politics engineer roles for working- and middle-class white women so that these women felt comfortable traveling on their own to Chicago for the Fair, and how did Holmes manage to lure such women to his bizarre hotel? How did the relative lack of building codes and inspections in Chicago provide Holmes an opportunity to lure, trap, and kill these women? Holmes was clearly sociopathic and/or psychopathic, but he was operating in a larger culture that, while it claimed to want to protect white women, had engineered—consciously or not—various systems that required all U.S. women to negotiate a world in which they were definitely not safe, even if they were sometimes made to feel they were. How did the powerlessness of women, relative to men—their lower incomes and inferior educational opportunities, for example—allow Holmes, as well as multiple other scammers and criminals who also worked the fair, to target and prey on women?

My thesis: While in our legal system, Holmes was ultimately responsible for the murders of these women, his crimes were facilitated by decades of cultural engineering of gender roles and other cultural practices, such as the aforementioned building codes and inspections.

A brief detour into pedagogy

One thing many of you might have found disorienting about HIST 100 is the kind of thinking the course asked you to do. You may have signed up expecting a course similar to history classes you had in high school: a chronological consideration of the human past around the world. Instead, you found yourselves on a series of islands in a metaphorical archipelago of topics—the practice of history, sacred spaces, water management, and the Fair—that we looked at using similar analytical and interpretive tools.

That model is actually closer how historians approach the past than is a typical high school history class. We consider larger cultural, environmental, political, and economic forces, but we focus in on particular places and moments to better understand the humans who came before us and how their decisions influenced our lives today.

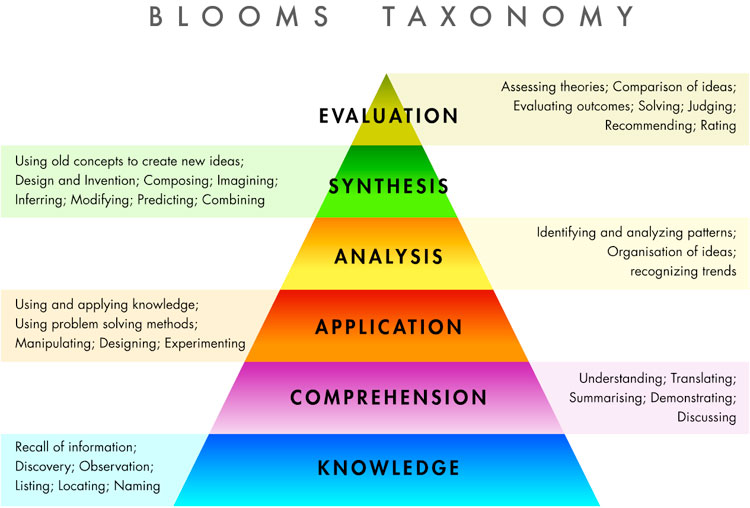

Pedagogically speaking, you might have come to expect that a 100-level course would ask you to read or listen to information on the course topic, then repeat it back—on quizzes and tests, in essays or reports, or through oral presentations—to the professor. In a 200-level course, you might be asked to demonstrate a deeper comprehension of the course topics and maybe even apply what you’ve learned to case studies or in labs. At the 300 level, you might expect to have to do some more complicated analysis, or to synthesize much of what you’ve learned from other courses in your major. And at the 300 and 400 levels, you could expect to create something of your own—to design experiments, craft a significant thesis, collect and interpret significant amounts of data for an original project.

Instead, HIST 100 asked you to do a little bit of all these things. One of the most common approaches to scaffolding a student’s education is represented by Bloom’s Taxonomy. Here’s a visual depiction of Bloom’s (click to enlarge it).

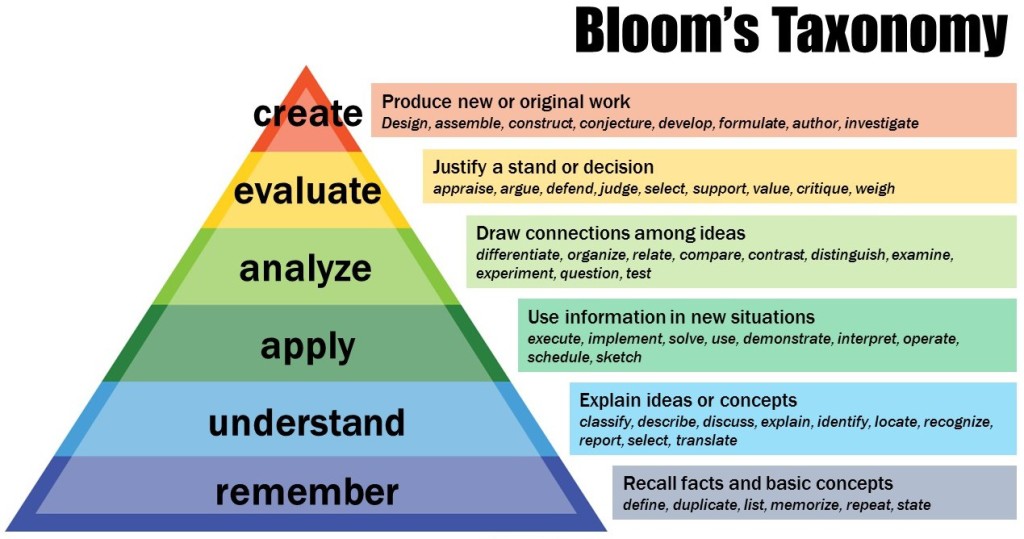

In recent years, educational theorists and practitioners revised Bloom’s, noting that synthesis often happens in the process of analysis, evaluation, and—the new capstone addition—creation:

As you may know, I’m not just a history professor; I also am director of a unit of the university focused on improving instruction at Boise State—and undergraduate education in particular. I strongly believe that, instead of expecting students to remain stuck practicing lower-level thinking skills (remembering, understanding, and maybe applying) during their first and sophomore years, every course at Boise State should push students toward higher-order thinking skills, including analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation.

Accordingly, HIST 100 asked you to use these higher-order thinking skills relatively early in the course (thinking about the Prownian analysis activity, for example) and is culminating in the creation of a final digital project that asks you to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate concepts surrounding the World’s Fair.

(Note that while I’ve asked you to stretch and develop these particular intellectual muscles, I’ve been grading this course as a 100-level course for non-majors.)

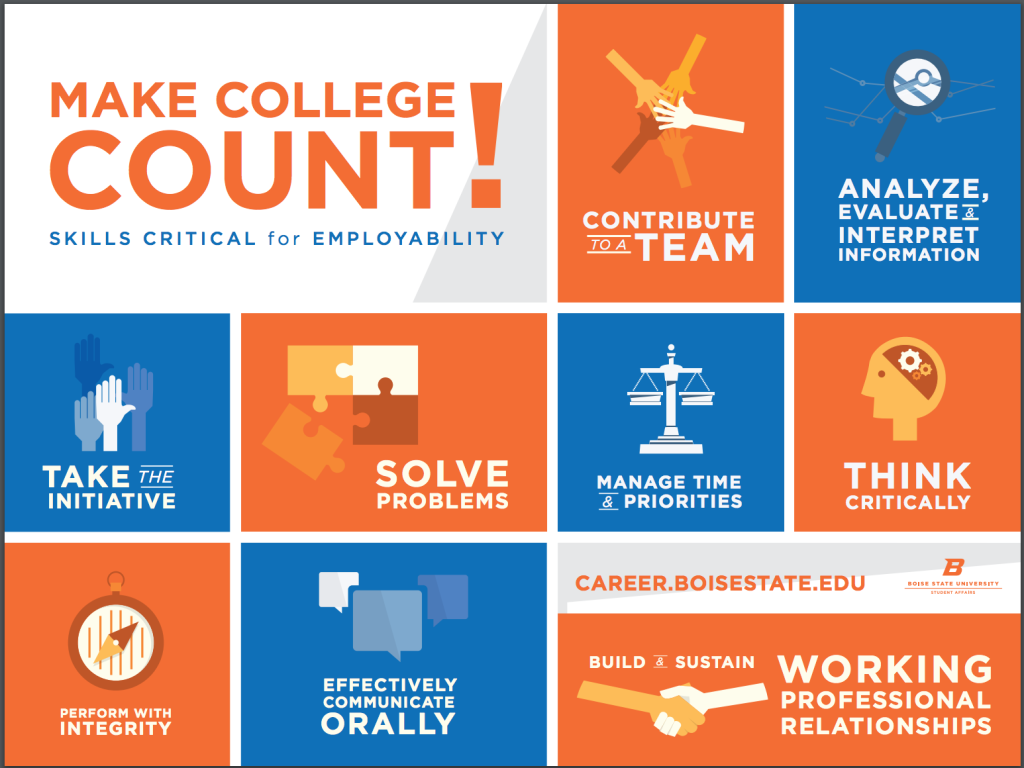

Skills for the workforce

I also designed the course activities and assignments to align with the kinds of skills employers expect college graduates to have developed. You can read about some of those on the website of the Boise State Career Center’s “Make College Count” initiative. (Click to enlarge the graphic.)

Going forward, beyond this course

I’m hoping that as you complete this course, you’ll take with you an appreciation for and a curiosity about the way others’ cultural habits, beliefs, and values have shaped your world. Sometimes you may share those values; other times, you won’t share them at all or even find them offensive. If at some point you buy a house at the edge of a new neighborhood, for example, you may be dismayed to find a few years later there’s a Jiffy Lube being built next door to your home. That’s a terrific example of habits (an automotive-focused society), beliefs (noisy and potentially stinky and polluting retail and service businesses are acceptable neighbors to a quiet neighborhood), and values (the rights of business owners and those engaged in commerce are just as important as those who live in an area).

Such habits, beliefs, and values aren’t only expressed via buildings, of course. Next time you’re about to cross a busy street, look down. Is there a curb cut with a small ramp that descends to street level from the curb? Are there little bumps on the ramp? Is the bumpy area bright yellow? This feature is a relatively recent addition to our cities. Rather than arising from nowhere, those tiny pieces of engineered landscape have a history. Why are they there? Whom are they meant to serve? And why haven’t they always been there? How did our collective habits, beliefs, and values shift in ways that allowed them to emerge as important, and often even required, pieces of the city hardscape? And who benefits? (Hint: Far more people than the wheelchair users or blind people using canes that the curb cut was designed for.)

Now here’s a harder question: Aside from the fact that an impressive, iconic tower had already been built in France, why did the planners of the World’s Fair not just build a higher tower? Or slides or a carrousel? Or any other number of impressive or entertaining structures? Why was Ferris’s proposal for a giant wheel so persuasive? How was it symbolic of larger cultural concerns and beliefs? With what habits, beliefs, and values did it resonate?

Thank you—and a small token of my appreciation

Thank you for sticking with me through this course; we didn’t have anyone drop out after the first week. I appreciate your continued and often enthusiastic participation, especially when a module was difficult or required a good deal of reading (as history courses tend to do).

I know I was slow in returning your assignments with comments, and for that I am deeply sorry. This is both my first time teaching an online course and my first time teaching a 3-credit course while also directing the IDEA Shop, and I really struggled with time management (as I know many of you do, too). As a token of my gratitude for your patience with me, I’m not applying lateness penalties to those of you who turned in a few blog posts late and/or who turned in one or two assignments late. (Note that this does not apply to the final group assignment, which has a hard deadline because grades are due to the registrar shortly thereafter. And students who regularly turned in assignments late will see a decrease in their grades because it’s not fair to the students who turned in almost everything on time if I pardon all lateness.)

And, of course, do come see me if you would like some assistance with or feedback on a draft of your final group project.

I hope you’ll consider taking other history or humanities courses during the rest of your time at Boise State. And if you feel you did well in my course or at least demonstrated considerably above-average effort in the course, feel free to ask me to write letters of recommendation for scholarships or awards.

Best of luck to you in the future! I hope our paths cross again. If you’re ever on the third floor of Riverfront Hall, please stop in the IDEA Shop to say hello.